In films about music, we often see virtuoso improvisation. It both attracts us and frightens us with its complexity. The Monkey Music team is ready to help you get rid of fear and tell you about improvisation in detail.

Improvisation is an impromptu activity based on fantasy and creativity. We meet her everywhere and we ourselves know her well. In music, improvisation is the creation of a musical form or its beating with musical expressiveness. The main means of expression are mode, harmony, rhythm, tempo, dynamics, timbre, articulation and intonation.

The basic point of musical improvisation is the concept of the hemispheres of the brain and two different approaches to improvisation. According to modern psychology, the left hemisphere of a person is responsible for logical, rational activity, and the right hemisphere is responsible for emotional and sensory. The approach to working on a particular piece and, in general, on developing oneself as an improvising musician will be based on these concepts.

Approach 1 – Left Brain

It involves the gradual assimilation of various ideas for playing musical material, and the musician draws these ideas from outside and most often in a rational way. In this approach, the idea of playing arpeggios of chords, or playing arpeggios of one chord while playing another, is common.

Most often it is called “vertical” – playing each chord in harmony in its own way – fret, arpeggio, pentatonic, etc. Such thoughts are based on music theory and are based on rational assumptions about euphony, phonic interest and astringency of sound. This is largely the result of experimentation with different modes and chord progressions. The advantages of this approach are the ability to quickly draw ideas from other musicians, as well as create your own by analyzing harmony, chord structure, modes, etc. The downside of using the left-brain approach often is creating “music” out of your head, without anticipation, feeling, or individuality.

True, very often in video tutorials and books it is said which fret or arpeggio to play over a particular chord, but rhythm and phrasing remain overboard. Rhythm should be understood as the rhythmic basis of the entire solo as a whole, and, more importantly, the rhythmic basis of each phrase. Not much attention is paid to the length of each phrase in metric units (how many measures should your phrases last). As a result, a beginner improviser finds himself in a situation where he does not know exactly what to do with one or another mode.

Let’s start with the length of the phrase. Here, of course, everything is individual, but many textbooks prefer two-bar phrases. A little later, you can try to “construct” four-measure phrases, but for now we will focus on two measures in 4/4 time. Two measures in 4/4 time are two whole lengths, four halves, 8 quarter notes, 16 eighth notes, and 32 sixteenth notes.

To start, take the traditional form of the twelve-bar blues and play only two-bar phrases in the tonal pentatonic or blues scale. Since we have fixed two aspects – the length of the phrase and the scale, it remains to decide on the rhythmic basis of the phrase. Start with long notes – play a whole note on the first beat of each bar and then pause in bars 3 and 4. Repeat the same further: 5th and 6th bars – whole notes, 7th and 8th – pause. Do the same for bars 9 to 12. Which notes to choose from the scale is up to you. Listen and experiment. It is better to start with the root of the currently sounding chord. Do it right now. Made? Congratulations – you’ve just played a conscious prepared rhythmic improvisation on a blues square. Next, play the halves, and then pause for two measures. Do the same with quarters, eighths and sixteenths. Take the time to stabilize this aspect of the game, and don’t forget the two conditions for successful practice: listen to what is going on and enjoy the practice.

Meteorhythmic playing is very important when developing a left-brain approach: start strictly on the first beat of the first, fifth and ninth bars and record the sound on the first beat of the third, seventh and eleventh bars. Do not try to play unevenly, swing beats, syncopate and bend with accents at this stage. To develop yourself as a performer, you can experiment with dynamics – make a crescendo to the end of a phrase, or vice versa diminuendo. A good trainer for dynamic nuance would be to play the first phrase on the forte, the second on the piano, the third on the mezzo forte, and so on.

When playing strictly on the first eighth becomes a simple and well-developed skill for you, you can afford metro-rhythmic development. Choose the phrases that you like the most and start them on the second eighth of the first bar. You will end, in theory, on “one and” in the third measure (well, and, respectively, the seventh and eleventh). You can make yourself a weekly plan – Monday 1, Tuesday 1 and Wednesday – 2, etc. (metric fractions where you start play phrases). To be certain, play only eighth durations all week. I am sure that such a “limited” game (which actually gives you a huge amount of meter-rhythmic flexibility) will give you a lot of fun. And, most importantly, now your melodic lines will have a strictly defined rhythm and occupy a certain place in the “grid” of the entire musical form.

The next step is rhythmic ingenuity. Open the book of solfeggio exercises and play all the same simple scales – pentatonic or blues scale – in normal and reverse gallop, dotted line, eighth and quarter triplets, sixteenth quartoles with missing first, second, third and fourth notes, etc. Combine rhythmic figures in various combinations, still strictly observing the phrase length of two measures. Calculate pauses to yourself in quarters – this will develop your sense of musical time. Professional musical performance, like high-quality improvisation, is always rhythmic or rhythmic. So by improvising with rhythmic figures and patterns, you develop as a musician as a whole. All rhythmic figures will come to life under your fingers, becoming a part of you even more. To stabilize rhythmic thinking, we give examples of simple rhythmic patterns in 2/4 time.

Musical improvisation. The concept of the hemispheres of the brain. rhythmic thinking. Creativity, of which music is a part.

You can use them to work out any frets or arpeggios.

Start experimenting a bit with a left-brained approach to creating your own phrases. Even if it seems to you that this is not a “real” improvisation, then over time you will feel what great opportunities this method gives. Combine rhythmic patterns with dynamic nuances, and then try shifting all the resulting phrases to different beats.

The last aspect of a rational approach to phrasing is articulatory nuances – strokes or types of sound production that you use to play your lines. Set yourself conscious goals – to play the entire two-bar legato, non-legato, marcato, tenuto, staccato, etc.

Musical improvisation. The concept of the hemispheres of the brain. rhythmic thinking. Creativity, of which music is a part.

Decide for yourself which beats to emphasize. At first, act very consciously and rationally. Use the articulation you want, listen to what is happening. Soon your ears will be “telling” your fingers which strokes to use. So, within the framework of the left hemisphere approach, you can thoroughly “pump” your rhythm, articulation and dynamics.

Approach 2 – Right Brain

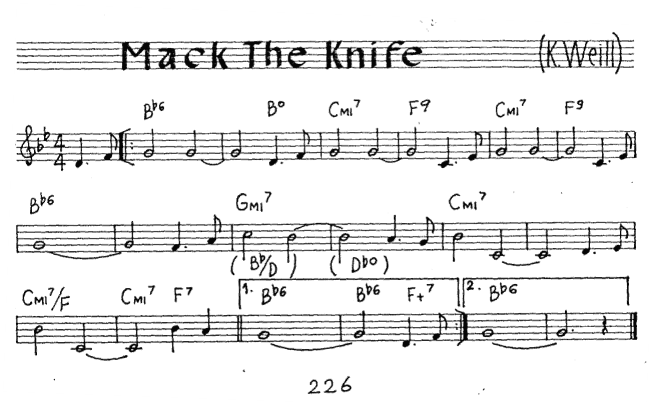

I think this approach is more musical, sincere and individual. Since we are discussing the topic of playing around with a ready-made musical form (say, the jazz standard “Mack the knife”), we first need to break it down into individual chords. Next, try to beat each chord separately, forgetting what it is called, what its function is in the harmony and structure of the piece, etc. For example, in Kurt Weill’s piece “Mack the knife” the first chord is the tonic Bb6.

Musical improvisation. The concept of the hemispheres of the brain. rhythmic thinking. Creativity, of which music is a part.

The right-brain approach is that you play a chord on the piano or guitar (even if you are a wind player or a violinist, you need a general knowledge of any harmonic instrument – keyboards are the best option) or enter it in the simplest, best choral texture, in which or a sequencer and listen carefully to yourself. Try to hear the musical ideas that will sound in your head. When working with a right-brain approach, one must be sincere and honest, not allow oneself to think that the same Bb6 chord is now playing, consisting of the notes of Bb, D, F and G, and therefore any combination of them will sound good .

The action plan is:

– play a chord

– listen to its sound, feel its flavor and mood;

– sing the phrase that will appear in your imagination in response to this chord;

– find the notes you sang on a musical instrument;

– play them with different articulation strokes and using different fingerings;

– memorize the received phrases, write down the best of them with notes;

– use the best of the received phrases as blanks;

In the case of the second, intuitive approach, one must consciously abstract oneself from the use of articulation, rhythmic basis, phrase length, etc. The articulation and dynamics you will get are those that you have practiced the most before – consciously or not, the rhythmic basis of the phrases will come from the subconscious.

Your musical subconscious and its content depends on you personally. It is determined by what kind of music and what artists you listen to, what you pay attention to, in what musical environment you are. As Boris Grebenshchikov sang in one of the songs, “you will need a guide-interpreter when you come to your senses.” We recommend talking about musical tastes and specific recordings with experienced musicians and educators who work in your style and others. Do not be afraid to develop and learn something new from music professionals. By intelligently combining the study of the diverse world of music with individual lessons, you will not lose yourself, but rather find yourself. As Friedrich Nietzsche said, “Most people think they have found themselves before they even start looking.” Do not repeat their mistakes – develop! And get your own improvisational style as a reward.

These approaches are the main ones in mastering musical improvisation. Which one you prefer is up to you. The advantage of the left hemispheric method is the ability to practically endlessly enrich the world of one’s own improvisational ideas. The advantage of the right-brain method is the ability to listen to yourself, create your own improvisational world, discover individual intonations, rhythmic patterns, articulatory nuances, etc.

At first, many musicians are not sure about their improvisation. Therefore, they should start with the first, rational, method of constructing phrases. Especially when it comes to collective playing with other musicians – here it is better to have developments that sound good and are consistent with the sounding harmony. Therefore, it is worth playing the “correct” scales, and also not neglecting other people’s “branded” faces. As the speed of thinking develops in creating your own phrases, you should devote more and more time to the second, irrational method – this will lead to the development of musicality, the connection of the inner ear and the head with the fingers, the acquisition of a special musical courage, as well as an incredible feeling of joy from the possibility of creating an improvised solo ” Here and now”.

Of course, the best option is a reasonable combination of the two concepts. Getting acquainted with the vertical methods of playing harmonies, you should play them, sing them, listen to the sound and leave in your arsenal those that are to your liking. Excessive “immersion” in oneself can lead to monotony and predictability of improvisation. So, when listening to other musicians and getting to know their improvisational ideas, don’t forget to listen to yourself, and at the same time try not to overdo it.